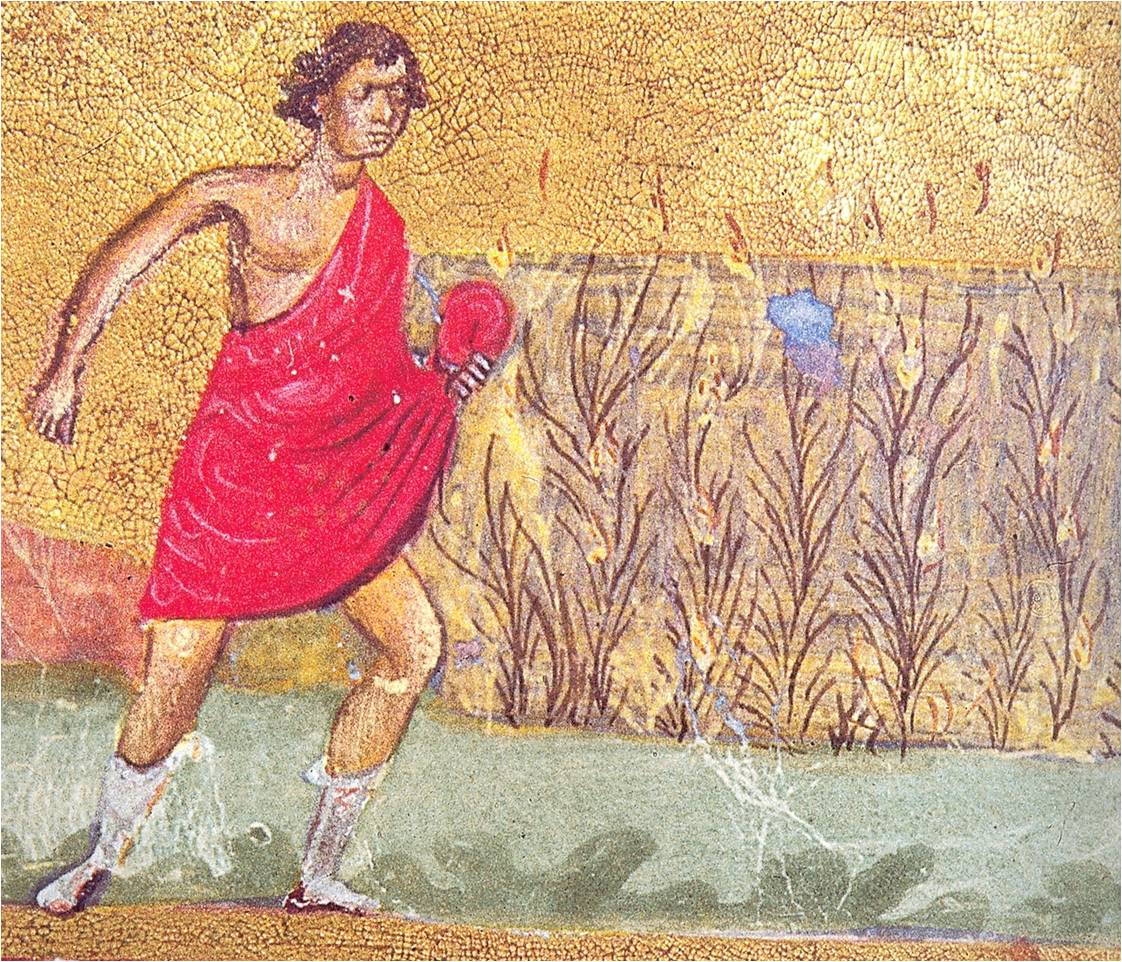

The harvesting process was carried out in the month of June with the use of a sickle.

Name - Origin

Σίτος, σιτάρι.

The following varieties of wheat existed in Cyprus: 1) tripolitis, 2) vroullias, 3) psathkias, psathas, psahas, kotshinon, kotshinin or kotshinositaron 4) tz̆yperounda, 5) eftakoutsoullon, 6) mavrotherin, 7) skalavatis, 8) muskoïkon or asprositaron, 9) kambouriko or kambouris, 10) saipin (Papacharalambous 1965, 207).

Scientific name: Triticum vulgare or Triticum satirum of the Graminae family (Agrostodi) (Kyprianou 2003, 65)

The harvesting process was carried out in the month of June. Harvesting was done using a sickle, which was an exhausting task that required the contribution og the whole family aa well as the harvesters (Kyprianou 2003, 65-66).

Functional and symbolic role

The cultivation and consumption of wheat was introduced to Cyprus from the Middle East during the Bronze Age. The writings of Archimandrite Kyprianos and Athanasios A. Sakellariou record the euphoria of Cyprus in terms of wheat, especially in the area of Mesaoria, and the production of sufficient quantities, which could last for more than a year if the wheat was not exported or damaged by locusts (Arch. Kyprianos 1788; Sakellariou 1855). Cyprus used to export large quantities of wheat and barley, especially from the Mesaoria region. Archimandrite Kyprianos reports that large quantities of wheat and barley were loaded on many ships to other countries (Arch. Kyprianos 1788, 535). Women used wheat to prepare kollyva for memorial services and for saints' feasts. On on New Year's Eve, they would also prepare kollyva in honor of Agios Vassilis (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, 106).

After the end of the harvesting process, a feast was held where workers and farmers would celebrate the end of the production cycle. At the feast they sang, with violins and lutes, consuming wheat preparations such as pasta and everyone would wish the owner to have a successful future harvest (Ionas 2001, 71-72).

During a wedding ceremony in the church, wheat and cottonseed were thrown to the newlyweds as wheat was a symbol of fertility (Mavrokordatos 2003, 333; Christodoulides 1999, 117)

The bread and other wheat products that housewives used to make show the symbolic use of wheat. Wheat signifies happiness and the warding off of evil. In some villages, after a baby was born, it was placed in a trough along with wheat for 40 days to protect it from evil (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, 155, 157). It was believed that the baby would have wealth in life, since wheat in the rural society of Cyprus meant wealth. It also served as a wish for the baby to live well and have many children. This wheat would be the basic pay to the midwife which could be supplemented with an additional sieve of wheat or more, accordingly (Protopapa 2009, 148-149, 212, 215-216, 229, 331-333, 353).

After childbirth, the midwife or another woman would throw seeds to the new mother, the most common of which were wheat, nigella and cotton seeds. They were considered a blessing from God and that the blessing would be carried to the new mother. Wheat was also used in weddings to wish the bride to have many children. In some villages, when an infant had its first tooth, they would dress the infant in red and bathe it with boiled wheat. Then they would thread 32 grains of wheat, the same as the total number of teeth, hang the thread on the infant's cap and make a wish that the infant's teeth would grow quickly and painlessly (Protopapa 2009, 148-149, 212, 215-216, 229, 331-333, 353).

On New Year's Day the farmers used to make kollyva for Aguos Vasilis (Santa Claus) and used to pour a few grains of their best wheat into the thyme that covered the mouth of the pitcher. These grains would get wet every time someone tilted the pitcher to get some water and they would slowly sprout. On the day of the feast of Saint Anthony on 17 January, the thyme and the seeds were removed from the mouth of the pitcher and taken to one of the farmer's fields, usually the best one, and planted. Some even say that the wheat from these seeds was harvested separately and the wheat was kept to be replanted the same way for seven consecutive years. It was believed that the blessing was great and the grain would grow into gold.

Additional information and bibliography

Archimandrite Kyprianos (1788), Ιστορία Χρονολογική της Νήσου Κύπρου, Evagoras press, Nicosia.

Ionas, I. (2001). Παραδοσιακά επαγγέλματα της Κύπρου (Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research XXXVII), Centre for Scientific Research, Nicosia.

Kypri Th. - Protopapa K. A. (2003), Παραδοσιακά ζυμώματα της Κύπρου. Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XVIII, Nicosia.

Kyprianou Th. Ch. (2003), «Το σιτάρι», Λαογραφική Κύπρος 33,53, 64-69.

Mavrokordatos G. I. (2003), Δίκωμο: Το χθες και το σήμερα, Nicosia.

Papacharalambous G. Ch. (1965) Κυπριακά ήθη και έθιμα, Cypriot Studies III, Nicosia.

Sakellarios A. A. (1855), Τα Κυπριακά: Ήτοι πραγματεία περί Γεωγραφίας, Αρχαιολογίας, Στατιστικής, Ιστορίας, Μυθολογίας και Διαλέκτου της Κύπρου. Εις τρεις τόμους, τ. 1, Aggelopoulou press, Athens.

Christodoulides Chr. (1994), Πέλλα-Πάις, Limassol.

Dimitra Demetriou, Dimitra Zannetou, Stalo Lazarou, Savvas Polyviou, Argyro Xenophontos