Flour has always been the basic raw material for the preparation of various doughs, most notably for bread.

Name - Origin

Αλεύρι.

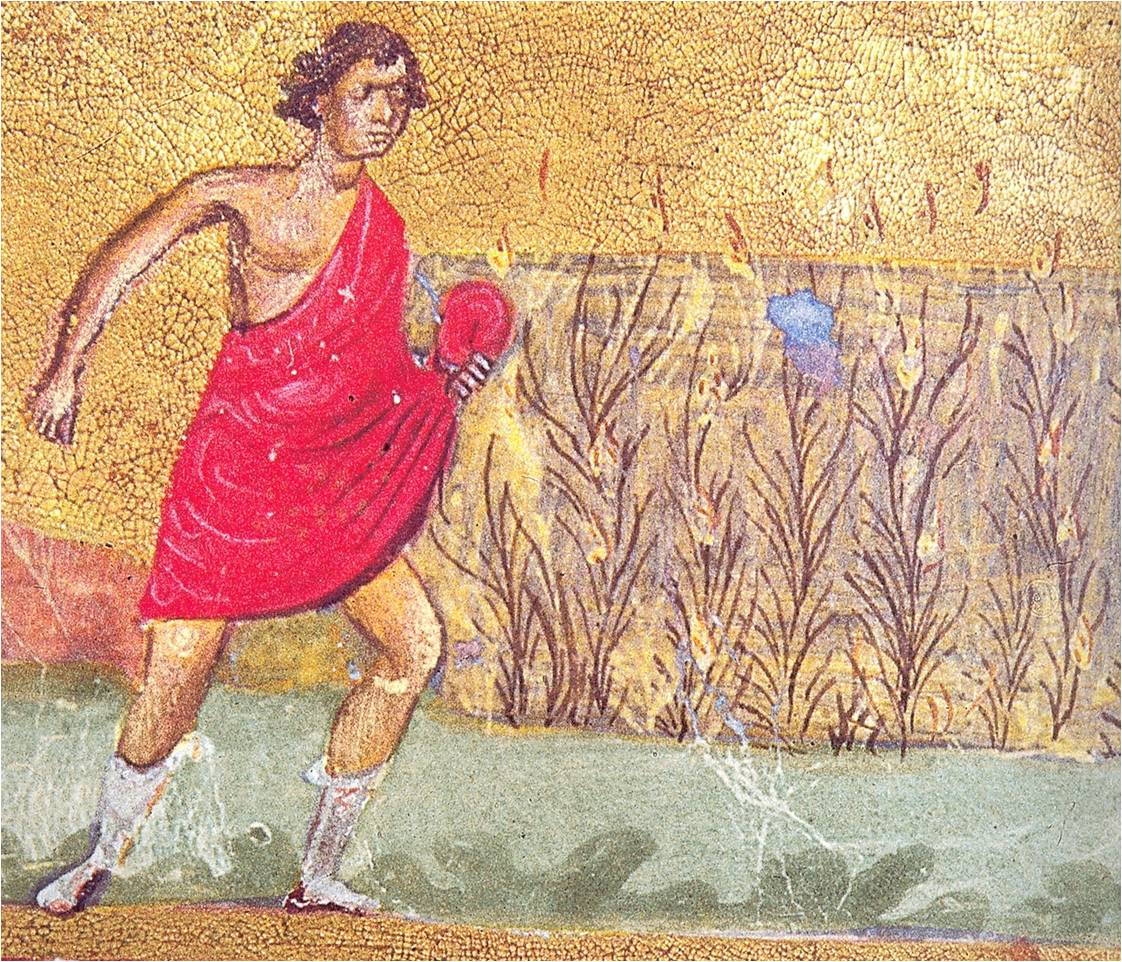

Flour has always been the basic raw material for the preparation of various doughs, most notably for bread. Bakers used wheat flour bought directly from producers or mills and would usually try to choose the best flour available on the market. Farmers, on the other hand, were obliged to use wheat and flour of their own production, which in terms of quality could be less than perfect. Bakers would select the whitest of the grains and would ensure that a good mill would be used to produce semolina flour, which was twice sifted through the tats̆ian so as not to contain any bran. This is how luxury bread was made and was mostly consumed by the bourgeoisie. Brown bread was made with 3-to-1 semolina and fouskarin. Fouskarin was the flour containing ground bran and its colour was somewhat darker. But this brown matz̆ipa bread was whiter and softer than the bread made by/for the majority of the rural population which contained barley flour (Ionas 2001, 203).

Functional and symbolic role

At weddings, the relatives of the couple, apart from a sum of money, would also give some kanís̆s̆ia (gifts), for example food, which most of the times was flour (Protopapa 2005, vol. B, 275). For the Wednesday table of the wedding, in some villages, they would collect chickens from the villagers and flour to make pittes. In some villages the flour was brought by the best man and the maid of honour (Protopapa 2005, vol. B, 304).

In order to cut a baby's nails, they would, first, dip them in flour. They believed that the flour would protect the baby from evil spirits. Later on, the initial purpose was abandoned and they would justify this action by claiming that it would help the baby's nails to be white (Protopapa 2009, 350).

A second symbolic practice relates to the need to protect the flour. In Cyprus, once a load of flour had been transported from the mill to the house, no one was allowed to touch it so as not to spoil it. A key or a metal object had to be thrown on the flour before anyone could touch it. The only explanation about this belief and custom is that the metal acts as a deterrent to the prevalence of evil spirits, which according to popular belief could contaminate the flour (Papacharalambous 1971, 239).

Additional information and bibliography

Towards the end of the Ottoman period, Nicosia had a special flour market (bazaar) in front of Petestan, which was supplied by the mills of Kythrea. Wheat flour was mainly supplied, as well as barley flour in small quantities. In the years of the British rule, the colonial administration would purchase wheat and have it ground to flour to be stored in warehouses of the 'Control on supplies' service it had organised. This flour was given to bakers at a special price, thus, ensuring a steady supply of bread for the urban centres. In earlier times, when the dekáti tax was still in force, the concentration of large quantities of grain in state warehouses helped the bakers to obtain wheat, even though they had to have storage space. Later, this system changed and bakers were obliged to buy wheat instead of flour, after obtaining a special voucher that would provide them with specific quantities of wheat from the state warehouses. The quantities authorised to each baker were based on his customer numbers and, thus, there was no room for exploitation by fraudsters. It should be noted that the government was selling the wheat to bakers at a price below cost, while at the same time, fixing the selling price of bread. City bakers, who used to obtain flour directly from the mills of Kythrea, had no longer any interest in buying flour on the open market and were obliged to hire out the services of 'kkiratzídes' (transporters) to/from the mills. Those kkiratzídes who were supplying the bakers limited their visits to villages and would visit only those villages with a low or no cereal production.

From the 1960s onwards, bread making at home was becoming rare and all the baking was done by bakeries. Not just for bread but also for artos, prosfora, pannihides (bread types related to church offerings or festivities). Some bakeries today prepare the traditional Easter flaounes along with pastries and sweets, just like the European-style bakeries do, so now we have bakeries - pastry shops and not just bakeries. The traditional koulourádes (traditional bread makers and sellers) have disappeared and along with them the traditional koullouria, glistarkes, tashinopittes, elliopittes, which are not made by specialised micro bakers any more, but by bakeries. Similarly, unleavened bread, which in the past was prepared in the form of a pitta and baked on a stone slab or on the satz̆i, is now made in bakeries and used to produce the well-known pitta for souvlakia in a moderately hot oven. Nowadays, in the cities many housewives who want to bake the traditional flaounes or Sunday roast, take them to the local bakery to bake them for a fee. This applies to all traditional preparations (Ionas 2001, 205, 210-211).

Ionas, I. (2001). Παραδοσιακά επαγγέλματα της Κύπρου, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research XXXVII, Centre for Scientific Research, Nicosia.

Papacharalambous G. Ch. (1971), «Ο Χάρωνος οβολός», Cypriot Studies ΛΕ΄, 213-250.

Protopapa K. (2005), Έθιμα του παραδοσιακού γάμου στην Κύπρο, vol. A’-B’, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XLV, Nicosia.

Protopapa K. (2009), Τα έθιμα της γέννησης στην παραδοσιακή κοινωνία της Κύπρου, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XLIX, Nicosia.

Demetra Zannetou, Tonia Ioakim, Ivi Michael / Stalo Lazarou, Petroula Hadjittofi, Argyro Xenophontos