In the villages of Paphos district and Rizokarpaso area, olive oil production was inadequate; housewives would, therefore, use olive oil just to flavour their salads and vegetables, while they would use pork fat for frying (Xioutas 1978).

Name - Origin

Ελαιόλαδο.

When Cypriots wanted to differentiate olive oil from other types of oil, they would refer to it as "ládin kaló" (good oil) or simply "ládin" (oil).

Owners of small pieces of land and their families would begin to collect the olives for the production of olive oil in late autumn. A landowner would shake the branches of the trees, while women - the olive pickers - would collect the fruit from the ground (Hadjicostas 1995, 150-151). They would then take the olives to the olive mill for the production of olive oil. Nearly all of the villages had an olive press with either wooden or stone presses. The process would consist of cleaning the olives, crushing the fruit, adding water, pressing the olive paste and finally separating the olive oil from water (Ministry of Agriculture, 2000). One oka of olives would produce about 100-130 drams* (300-400 gr) of olive oil (Hadjicostas 1995, 151). "We would wash the olives that were to be used for the production of oil, we would then put them in the baskets and drain them and take them to the mill. It was a covered mill where a mule was used. They would check them, then they would put them on black clothes (like blankets), and fold them on either side to extract oil. For every litra of oil produced, one onja was given to the mill owner. A litra is two and a half okas; there was also militron (half a litra)" (Mavrokordatos 2003, 311). *Note: 1 oka = 4 onjas = 400 drams

Functional and symbolic role

In the villages of Paphos district and Rizokarpaso area, olive oil production was inadequate; housewives would, therefore, use olive oil just to flavour their salads and vegetables, while they would use pork fat for frying (Xioutas 1978). In contrast, in the villages of Mesaoria and the Nicosia district, olive oil was widely used in cooking. Olive oil was used to make ladopittes or kattimerka, ie. a sheet of dough spread with olive oil and baked in the oven or on the satz̆in and served with sugar or epsima (Athanasiadou 1985, 88). In Rizokarpaso, they used to prepare lytratz̆énes pittes using the first batch of oil extracted [lytratz̆éni = unleavened, i.e. without sourdough starter] (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, 294). During the harvest period, while in the fields, the family would eat plain dry bread with olives, onions, figs and oranges. Cooked food, which was usually pulses, would be eaten when they would return home (Hadjicostas 1995, 151).

The farmers would pay the miller according to the amount of olive oil produced. For every twenty litres of olive oil produced, one litre would be given to the miller. In addition, the olive growers were obliged to provide food for the mill's workers; the breakfast usually consisted of bread with olive oil and olives, while pulses or potatoes constituted lunch or dinner (Hadjicostas 1995, 153).

After the birth of an infant, it was customary that a new mother would offer to the midwife some olive oil too (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, 167).

Olive oil was added into the clay pots where halloumia were stored, so as to avoid worms (appeytoúrka) (Mavrokordatos 2003, 314).

"Following the collection of olives, the owner would invite all the people who had helped to his place and the hostess would prepare laópittes, makarónia, pis̆íes, xerotíana with olive oil" (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, 293-294).

- Olive oil is used by the church and the people to light the vigil oil lamps.

- Infants who could not speak, walk or were too weak were taken to church to place oil from a vigil oil lamp on them; they would take the infants outside the church, hold them upside down and pour the oil from the vigil oil lamp on them.

- When a newborn was sick and looked like it would die, they would rush to baptise it. One way of baptising the newborn was to sprinkled the infant with water and oil from the vigil oil lamp and used the oil to form crosses on its body.

- During the christening of an infant, the godfather would take oil to the church in a dish to be poured into the baptismal font the priest would cross the child with oil (Protopapa 2009, 100,109, 211, 231, 233, 233, 335, 414, 462-463, 477, 482, 527, 558-560, 564-568, 574-575).

Ioannis Ionas also notes that, in people's perception, olive oil was sacred and precious. Its sacredness is emphasised by the fact that every producer who went on a pilgrimage either to a chapel near his community or to remote monasteries would take with him oil in a bottle to light the candles in front of the icons. The oil was an offering so as to receive a blessing from the divine for abundant production. No one would accept to give oil from his house after sunset, and if anyone's oil container would break by mistake, it was considered to be a misfortune; great evil was foretold for the house, for the family that is (Ionas 2001, 216).

Additional information and bibliography

They used to anoint the newborn with olive oil. The midwife would apply oil on the baby or the people who were present would dip their finger in the oil and anoint the baby, giving the baby their blessing. They would also mix the oil with salt to anoint the baby. In some villages they would first anoint the baby with oil, then with salt and wine, and then bathe the baby, repeating this process for 40 days. After childbirth, it was common practice to apply soufes to the mother, i.e. poultices and suppositories on the mother's genitals. These were wrapped in a cloth smeared with oil and placed inside the vagina or the new mother would sit on it, to warm herself up and cauterise herself. It was believed that this procedure would prevent infection and the uterus would resume its position. When a child had abdominal pain, they would rub it with olive oil or put some oil in the child's navel. Mastic oil was also used for rubbing. In the village of Melanagra, oil from the vigil oil lamp of Virgin Mary of Kanakaria was used to make a cross on the baby. Infertility has long been a plague and a curse for a family, especially for a woman. Suppositories were one of the methods used to deal with this problem. They would use cotton or cocoon with hot oil or mastic oil (Protopapa 2009, 100,109, 211, 231, 233, 335, 414, 462-463, 477, 482, 527, 558-560, 564-568, 574-575).

George I. Mavrokordatos in his book "Δίκωμο: Το χθες και το σήμερα" (Dikomo: Yesterday and Today) notes that people were using oil for ear pain and abdominal pain (Mavrokordatos, 2003, 311).

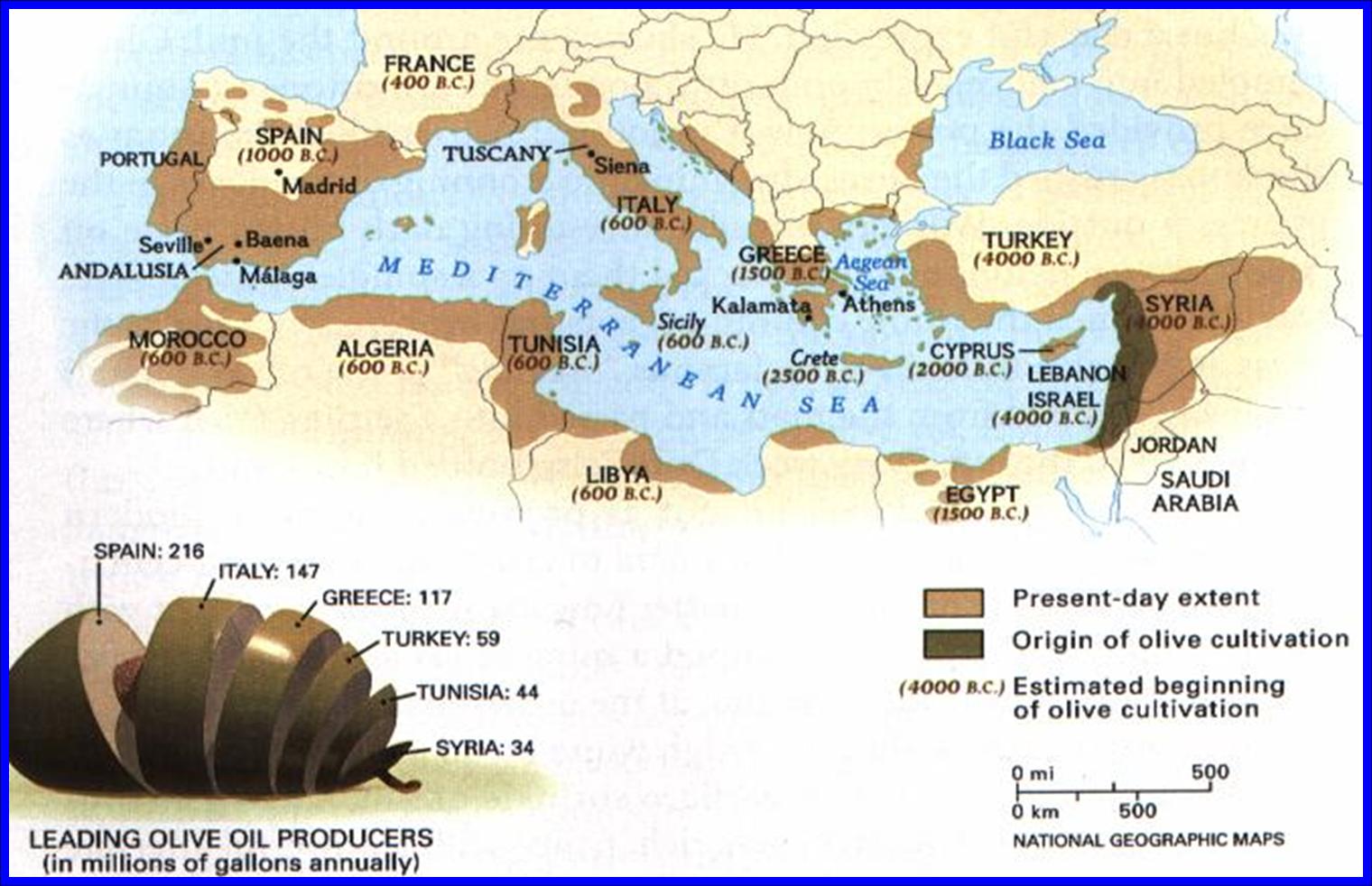

Archimandrite Kyprianos, in his 'History', published in the 18th century in Venice, gives information about the production of edible oils on the island; olive oil and sesame oil: "The olive groves yield a sufficient quantity of oil so that, when they prosper, the production of oil is sufficient for three years, and sometimes it is even sufficient for exports [...] The oil of wild olive trees is excellent and fine. When sesame oil is used as oil lamp, it is better than common oil' (Archimandrite Kyprianos 1788, 538). However, a century later, the overabundance of olive oil that Kyprianos describes seems to no longer be the case. Athanasios Sakellarios (1826-1901), a scholar of Cyprus history and an author, states that in 1890 the production of olive oil, which mainly was originating from the north of the island and from the Paphos region, was barely sufficient for the needs of the island's inhabitants (Sakellarios 1890). Moreover, it seems that at the end of the 19th century the organoleptic properties of Cypriot olive oil were of questionable quality. The German Magda Ohnefalsch-Richter, who lived in Cyprus in the period 1894-1912, reported what A. Gandry had already noted in 1855 in his book Scientific Research in the East concerning the quality of Cypriot olive oil: "The art of keeping olive oil pure is unknown to them. They mix together the unripe green olives, the overly ripe ones and the ones that are shrivelled up. As a result, the oil produced is so bitter and has such a strong taste that a European living in a country full of olive trees is forced to import olive oil from France or Italy. The use of old, wooden presses are not frequently washed, and the olive oil has a rancid smell" (Ohnefalsch-Richter, 1994).

The list of products that were exported in large quantities from Cyprus during the rule of Franks or Turks does not include olive oil. The fact is not surprising, since the quantity of olive oil produced in Cyprus varies. Besides, the people in Cyprus had to consume other types of oil alongside olive oil, such as trimitheleo, bakolado and sesame oil which were mainly used when baking particular types of dough (Ionas 2001, 213).

Athanasiadou Α. (1985), «Συνταγές ζυμαρικών από κατεχόμενα χωριά της Κύπρου», Λαογραφική Κύπρος 15,35, 81-93.

Archimandrite Kyprianos (1788), Ιστορία Χρονολογική της Νήσου Κύπρου, Evagoras press, Nicosia.

Ionas, I. (2001). Παραδοσιακά επαγγέλματα της Κύπρου (Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research XXXVII), Centre for Scientific Research, Nicosia.

Kypri Th. - Protopapa K. A. (2003), Παραδοσιακά ζυμώματα της Κύπρου. Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XVIII, Nicosia.

Mavrokordatos G. I. (2003), Δίκωμο: Το χθες και το σήμερα, Nicosia.

Xioutas P. (1978), Κυπριακή λαογραφία των ζώων. Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XXXVIII, Nicosia.

Protopapa K. (2009), Τα έθιμα της γέννησης στην παραδοσιακή κοινωνία της Κύπρου, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XLIX, Nicosia.

Sakellarios A. A. (1890), Τ Τα Κυπριακά: Ήτοι Γεωγραφία, Ιστορία και Γλώσσα της Νήσου Κύπρου Από Των Αρχαιοτάτων Χρόνων Μέχρι Σήμερον, Τόμος Πρώτος: Γεωγραφία, Ιστορία, Δημόσιος Και Ιδιωτικός Βίος, Sakellariou press, Athens.

Ohnefalsch-Richter M. (1994), Ελληνικά Ήθη και Έθιμα στην Κύπρο, Μαραγκού Α. (μτφρ.), Popular Bank Cultural Foundation, Λευκωσία.

Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment (2000), The olive tree, Press and Information Office, Nicosia.

Hadjicostas L. (1995), "The olive tree in my village during the interwar period", Λαογραφική Κύπρος 25, 45, 149-154.

Dimitra Demetriou, Dimitra Zannetou, Stalo Lazarou, Savvas Polyviou, Argyro Xenophontos, Tοnia Ioakim