Harvesting of olives was usually taking place in two periods, according to the type of olives to be produced. In late August or early September, when olives were still green, Cypriots would pick a small quantity of olives to make tsakistés and kolymbátes olives, while at the end of October they would collect the black olives to make xidátes and koumniastés olives.

Name - Origin

Ελιά.

ETYM. medieval < ancient ἐλαία (Babiniotis 2005, entry ελιά,η, 587) Scientific name: Olea europaea L. In Cyprus eliá (olive) is also called arkoeliá, mazouliá, eliá ímeri (Hadjikyriakou 2007, 230-233).

Harvesting of olives was usually taking place in two periods, according to the type of olives to be produced. In late August or early September, when olives were still green, Cypriots would pick a small quantity of olives to make tsakistés and kolymbátes olives, while at the end of October they would collect the black olives to make xidátes and koumniastés olives (Hadjicostas 1995, 150).

In Dikomo village, from the 15th of August onwards, women would pick green olives in order to make tsakkistés olives. Black olives (table olives) would be collected from October to the 14th of November and then salted in order to be preserved. "We would wash the olives that were to be used for the production of oil, we would then put them in the baskets and drain them and take them to the mill. It was a covered mill where a mule was used. They would be checked, then placed on ts̆oúllies - black clothes (like blankets) which would be folded on either side to extract oil (Mavrokordatos 2003, 310-311).

Hand harvesting was used to pick olives reachable from the ground while the rest of the olives were collected after beating the fruit off the trees. The olives were transported home in sacks. There they were cleaned off from the olive leaves and separated into coarse olives, which would be prepared to be part of the daily diet, and those that would be taken to the olive mill to extract oil (Ionas 2001, 213).

Functional and symbolic role

Olives are prepared in various ways, such as tsakkistés, kolymbátes, xidátes and koumniastés. Tsakkistés olives are green olives that are crushed using a stone and then their bitterness is removed; they are served with finely chopped garlic, dry coriander seeds, lemon slices and olive oil (Ministry of Agriculture 2010, Preservation of olives, 4). Kolymbátes olives are green olives that after their bitterness is removed, they are stored in a container with brine, lemon juice and olive oil and served with olive oil, thyme or oregano (Ministry of Agriculture 2010, Preservation of olives, 4). Koumniastés olives are made using ripe black olives, which are washed using water, their bitterness is removed while in brine for 3-4 days and are then stored in a container with salt (Ministry of Agriculture 2010, Preservation of olives, 6). Xidátes olives are preserved in vinegar and brine once the flesh has been scored using a blade and the bitterness of the olives has been removed (Ministry of Agriculture 2010, Preservation of olives, 7).

During the harvest period, while in the fields, people would eat plain dry bread with olives (Hadjikyriakou 2011, 230-233).

Usually pulses were served for lunch or dinner together with olives (Hadjicostas 1995, 151).

Olive oil was also produced from the olives ( Hadjicostas, 1995, 149-154), while women would use olives to make eliópittes (olive pies) and eliotés. Eliópittes were rolled pies filled with olives and baked in the oven. The filling contained, in addition to olives, fresh coriander and onion. Eliotés were a type of bread kneaded with olives, fresh coriander and onion and baked in the oven (Athanasiadou 1985, 84).

Blessed olive leaves were included in home censers, which were widely used in Cyprus. "On Palm Sunday, everyone would bring olive leaves to the church and would leave them for forty days until the Ascension; they would then take the leaves home and use them in the home censer" (Mavrokordatos 2003, 311).

“On New Year's Eve (December 31st) in Rizokarpaso, the members of the family, together with other relatives and friends, would gather around the fireplace and try, while warming themselves, to foretell their future in the New Year by the method of empyromancy (divination by burning olive leaves), a popular divination method. Each person throws an olive leaf on the burning coals to ask Saint Vasilios, who is celebrated by our Church on the following day, "to show and reveal", whether the person (the name of whom they call while throwing the olive leaf), loves them or will give them poulistrenan. If an olive leaf, once heated, bounces with a crackling sound and turns over, it is believed that the saint's response is affirmative, that is, the person they called loves them or will give them poulistrenan. They believe that, the greater the crackling sound is, while the leaf bounces on the burning coal, the more is the love of the person. If, on the contrary, the leaf does not bounce, but is burnt on the spot, this is a sign of a negative response regarding that person, which fills them with great sorrow and sadness. They try several times to make sure that the response is ‘true'. While throwing the leaves on the burning coals, they say (there are several variations in different areas of Cyprus): "Ae Vasili vasiliá, you who went to Egypt and wondered in the desert and you who have seen the fortune of fortunes, show me my fortune as well, if x loves me, or if x (usually the godfather) will give me poulistrenan (gift, usually money). The custom of empyromancy, an old Byzantine custom, is widespread around Cyprus” (Taousianis 2008, 65).

On New Year's Eve, housewives used to decorate the front doors of their house with twigs from an olive tree. This custom of Byzantine origin brings happiness and drives away goblins. The green twig of the blessed olive tree remains there throughout the festivities as a rather particular Christmas tree (Yangoullis 2008, 54).

In Kalopanayiotis village, one of the birth customs was that when a boy was born, a wreath made of olive leaves would be hung on the front door of the house; when a girl was born, a white cloth would be hung on the door.

According to analog magic, the water that a baby would drink for the first time, would contain an olive leaf so that the baby would not be thirsty but cool like an olive tree. They would make a cross with two blessed olive leaves and put it under the new mother's pillow. In other villages, they would put three olive leaves instead of two, which symbolised the Holy Trinity and they would then use these leaves in their home censer. At the same time, after the delivery, they would call the priest to visit the new mother's house and bless her. Usually, a bowl with water with olive, basil, rosemary, rosemary or rose geranium twigs would be ready for him to perform the holy blessing (Protopapa 2009, 163, 170, 278, 414).

Before and immediately after a wedding ceremony, the bride was always arched, that is, she would sit with her head covered and would be very modest. The family had to persuade the bride to behave so, using various reasons. One of them was that if tshe was modest, then a good year for olives and wheat would follow. Just as the bride would be arched, so would the olive trees as they would bear a lot of olives (Protopapa 2005, vol. A, 353). In most regions of Cyprus, olive tree twigs were used to weave the wreaths of newlyweds until the beginning of the 20th century. The use of olive tree twigs for the wreaths indicates an attempt to transmit the tree's fertility, vigour, growth to the newlyweds. It was believed that the olive tree in particular would bring blessing for it was also blessed. Its use on the wreath would also bring peace between the newlyweds. People would, first, use the twigs of the olive tree and the vine to form the base for the wreath, and then they would attach some leaves as well. They were careful with both the number of twigs and leaves, as well as with where to position them, so as to form a cross or the Holy Trinity symbol. In some villages of Tylliria, the olive twigs for the wreaths were cut in an impressive way. The olive tree to be used had to meet certain conditions. In some villages, they were careful not to use twigs from a wild olive tree in order to ensure that the couple would have a peaceful life. In other places, they would choose a tree that was far from the village or that could not be seen from the sea, as otherwise the newlyweds would be harmed. In other places, they believed that the newlyweds should not see the olive tree for at least forty days.

In the villages of the Paphos region, they would collect leaves from the olive tree in the churchyard so that they would be blessed. The event involved the whole community so many people would gather to bring the olive twigs; the relatives, the best men and the musicians would definitely attend. The relationship between the people and the olive tree is very interesting: they would treat it as a person and have a dialogue with it. First they would greet it: "Good morning, my olive tree" if it was morning and "Good day" if it was noon. Then, they would announce to it that they were going to cut some twigs for the wedding wreaths. They would take with them wine, halloumi, meat and a bun. First of all, they had to treat the olive tree, so they would pour wine on its branches and say "Here's to you, my olive tree" or "Drink up, my olive tree, for giving us the wreaths." And while music was playing, a man would go up the tree and cut the twigs, dropping them on a piece of cloth which was spread out on the ground. Before cutting the twigs, they would form three circles and dance around the olive tree and then dance with while holding in their arms the twigs they had cut. Olive twigs as well as a red thread would be placed on the tray with the wedding wreaths that would be carried to the church. Starting from the beginning of the 20th century, the wreaths were made using white wax, but they always had olive leaves so as to be blessed (Roussounidis 1988, 25; Protopapa 2005, vol. B, 17-23, 27-29, 97)

The consolation meal served following a funeral consisted of black olives and bread. The perception was that the olives due to their black colour, symbolised the deceased and that is why they were served together with bread (Roussounidis 1988, 35-36).

Additional information and bibliography

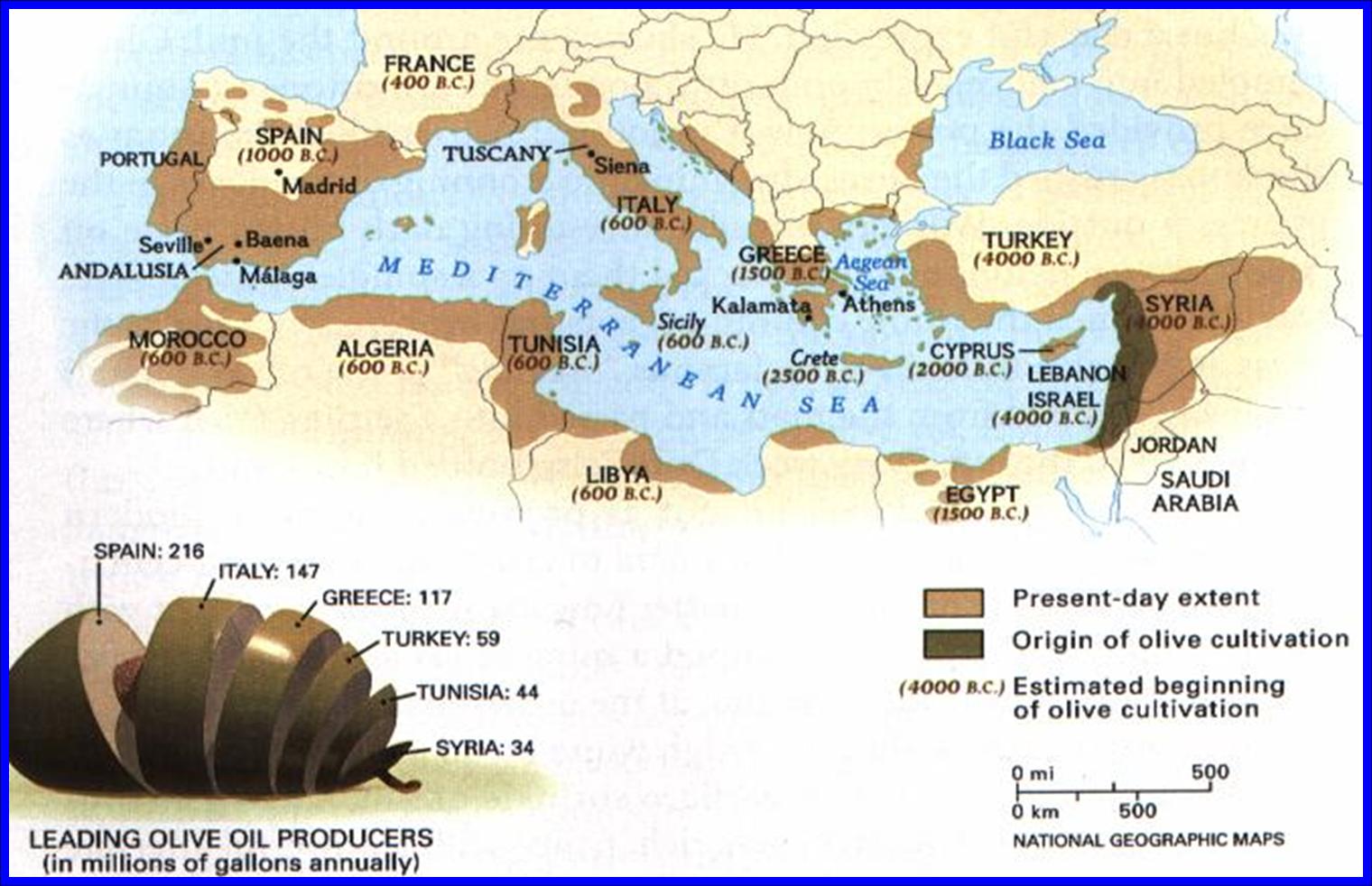

The olive tree has been present in Cyprus since the Neolithic period (6th millennium BC). Its cultivation began in the 2nd millennium BC, but the earliest evidence of oil production on the island dates back to the end of the 13th century BC, due to the first olive presses that were discovered in settlements and sanctuaries (Hadjisavvas 1992; Hadjisavvas 1996, 59-63).

It is worth mentioning that olive leaves were also used in folk medicine. Cypriots believed that olive leaf broth was helpful in cases of fever, while leaves and the root of wild olive trees could help with toothache. In the village of Tala in Paphos, people with hypertension used to chew 3-4 leaves from wild olive trees to reduce blood pressure (Roussounidis 1988, 57-59).

Attached article by Prof. Efrosini Rizopoulou Igoumenidou on the importance of the olive tree in Cypriots' everyday life.

Athanasiadou Α. (1985), «Συνταγές ζυμαρικών από κατεχόμενα χωριά της Κύπρου», Λαογραφική Κύπρος 15,35, 81-93.

Yangoullis K.G. (2008), Κυπριακά ήθη και έθιμα του κύκλου της ανθρώπινης ζωής, του εορτολογίου και των μηνών με στοιχεία γεωργικής λαογραφίας (Βιβλιοθήκη Κυπρίων Λαϊκών Ποιητών αρ. 67), Theopress Ltd., Nicosia.

Mavrokordatos G. I. (2003), Δίκωμο: Το χθες και το σήμερα, Nicosia.

Babiniotis G. (2005), Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας. Με σχόλια για τη σωστή χρήση των λέξεων. Ερμηνευτικό, Ορθογραφικό, Ετυμολογικό, Συνωνύμων-Αντιθέτων, Κυρίων Ονομάτων, Επιστημονικών Όρων, Ακρωνυμίων, Centre for Lexicology, Athens, Greece.

Protopapa K. (2005), Έθιμα του παραδοσιακού γάμου στην Κύπρο, τ. Α΄- Β΄, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XLV, Nicosia.

Protopapa K. (2009), Τα έθιμα της γέννησης στην παραδοσιακή κοινωνία της Κύπρου, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XLIX, Nicosia.

Rizopoulou-Egoumenidou E. (2005), "The role of olive tree and olive oil in the traditional life of Cyprus", Second International Conference, Traditional Mediterranean Diet: Past, Present and Future, focusing on Olive Oil and Traditional Production (Athens 20-22 April 2005).

Rousounidis A. Ch. (1988), Δένδρα στην ελληνική λαογραφία με ειδική αναφορά στην Κύπρο, τ. Α΄, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XII, Nicosia, Nicosia.

Taousianis Ch. (2008), Λαογραφικά σύμμεικτα Ριζοκαρπάσου. Αναφορές και σε άλλα μέρη της Κύπρου και του ευρύτερου Ελληνισμού, Nicosia.

Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment (2010), Διατήρηση ελιών και παρασκευάσματα από ελιές, Press and Information Office, Nicosia.

Hadjikyriakou N. G. (2011), Αρωματικά και αρτυματικά φυτά στην Κύπρο. Από την Αρχαιότητα μέχρι Σήμερα, Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation, Nicosia.

Hadjicostas L. (1995), «Η ελιά στο χωριό μου την εποχή του μεσοπολέμου», Λαογραφική Κύπρος 25,45, 149-154.

Hadjisavvas S. (1996), «Η τεχνολογία της μετατροπής του ελαιόκαρπου σε ελαιόλαδο κατά την αρχαιότητα στην Κύπρο», Ελιά και Λάδι. Τριήμερο Εργασίας (Καλαμάτα 7-9 Μαΐου 1993), Πολιτιστικό Τεχνολογικό Ίδρυμα ΕΤΒΑ – ΕΛΑΪΣ Α.Ε., Αθήνα, 59-69.

Hadjisavvas S. (1992), Olive Oil Processing in Cyprus: From the Bronze Age to the Byzantine Period (Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology XCIX), Paul Åströms Förlag, Göteborg.

Efrosini Igoumenidou, Eleni Christou, Dimitra Demetriou, Dimitra Zannetou, Stalo Lazarou, Savvas Polyviou, Argyro Xenophontos, Tοnia Ioakim, Petroula Hadjittofi