Bread during the Byzantine Empire

Name - Origin

Ψωμί, άρτος

Byzantine bread varied in quality, depending on the type of flour used and the method of milling the grain. There was bread made of wheat or barley (Motsias, 1998 p. 73)

Functional and symbolic role

Bread formed the basis of the Byzantine diet. In the poems of Ptohoprodromos (Koukoules 1952, pp.12-29) a distinction is made between ‘white’ and ‘brown’ bread. White bread was a luxury item and was intended for the wealthier class of citizens, while brown bread was a lower quality bread and is described as ‘bread of the poor’; there was an even lower quality bread than brown bread which was described as ‘hondróhylo’ (coarse bread). Although brown bread was nutritionally richer than white bread, the poet complains about his poverty:‘they have the semidalin (semolina) bread, we have the pityrounda (bran) bread’

Strict fasting was followed in monasteries, where the most common food was agiozoúmin (a broth of water, oil and thyme), in which bread crumbles were added to make the food more filling (Hesseling and Pernot ,1910 pp. 61-62)

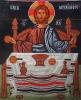

Leavened bread, i.e. prósphoro, which is sealed on top with the letters ΙC ΧΡ ΝΙ ΚΑ, is used together with wine (anáma) during the Eucharist service in commemoration of the redemptive death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. During the Eucharist, bread and wine, by the action of the Holy Spirit, are transformed into the ‘body’ and ‘blood’ of the Lord (Phidas, 2002)

Additional information and bibliography

In Byzantine iconography, the depiction of spherical-shaped bread (often with a cross-shaped seal in the top centre) in scenes of the Last Supper, the Wedding at Cana or the Divine Communion is very common and mainly symbolic. However, in churches in Cyprus and elsewhere, we observe a notable increase in the number of spherical breads in scenes of the Last Supper (one in front of each attendant) dating to the Middle Byzantine period (9th-12th c); several scholars conclude that these were slices of bread which were used as plates (for placing small portions of food on them) and then eaten by dipping them in sauce (Vionis, 2001 pp. 87-88)

D.C. Hesseling & H. Pernot (1910) Poèmes prodromiques en grec vulgaire. Amsterdam: Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen 11.

F. Koukooules (1952) Βυζαντινών Βίος και Πολιτισμός. Τόμος Ε. Athens.

Χ. Motsias (1998) Τι έτρωγαν οι Βυζαντινοί. Αθήνα: Kaktos Publications.

Β. Phidas (2002) Εκκλησιαστική Ιστορία. Εκδόσεις Διήγηση, Athens.

A. Vionis (2001) “Post Roman Pottery Unearthed: Medieval Ceramics and Pottery Research in Greece”. Medieval Ceramics 25, σελ. 84-98.

Athanassios Vionis