Every part of the animal, even the theoretically useless parts, such as the ears, the intestines and the feet were important and useful.

Name - Origin

Χοίρος.

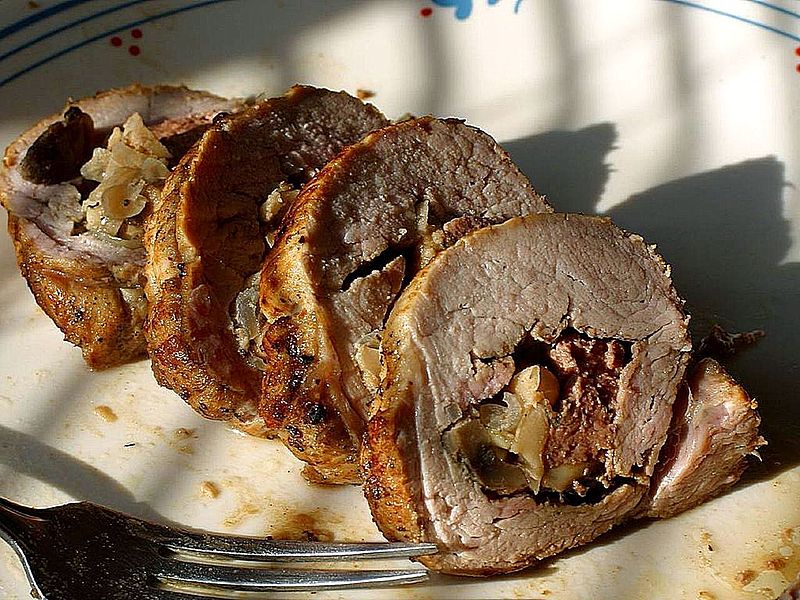

They would cut the pig into pieces: head, legs, intestines and the bladder (which the serlákkis i.e. butcher would clean, blow and give to the children to play football with it). The intestines would be washed thoroughly and placed in vinegar. The chopped pieces of pork meat would be soaked in wine for eight days; then, the intestines would be filled with this meat to make sausages. The sausages and the rest of the meat parts would be hung on a pole and then smoked over fire with s̆s̆innos, mersinin (myrtle) and xistarka twigs. They would then be hung in the sun to dry thoroughly. A pig would provide pork meat to a household for a year (Agia Varvara Primary School 1991, 45).

The meat parts that would be cured and also lountza and loukanika (sausages) would be placed in large wooden troughs (tamarin) together with sterkón wine to soak in the wine for 2 to 3 days. The meat that was to be cured would be removed from the trough and hung in the sun for another 4 to 5 days, after any fat had been stripped off completely. Then, the pieces of meat would be placed in a clay pot which used to be coated internally, called koúmna (hence, these cuts were called koumniastá) and they would be covered with myllan (fat) and stored in a cool and dark place in the house.These pieces of meat would later be prepared and served as part of the family's meals. Lountza and the thigh pieces which would be used to make hiromeri and posyrtin, would be hung over the fireplace. Olive, carob or cypress wood would be used to light the fire, which would give these cuts a distinctive smell and taste. The animal's skin with fat remains would be used to make titsiries and also myllan (fat) that would be used to cook with as a substitute for oil and on bread as a substitute for butter. Titsiries would be eaten with bread, black olives and tomatoes and were also used to make sweets, called titsiropitta. Glytžia (the throat glands) and the sweetmeats were used to make aphelia or mezé dishes. The head, feet and ears of the pig were used to make the famous zalatina. Search for lountza, hiromeri, posyrti, koumniasta, mylla, titsiria (titsiries), titsiropittes, glytžia and zalatina in the Foods section and in the Traditional Recipes section.

ETYM. < hiros (pig) (Yangoullis 2009, entry σ̆οίρος,ο - σ̆οιρίν,το, 435)

A small pig is called σ̆οιρίν (s̆irín) (Yangoullis 2009, entry σ̆οίρος,ο - σ̆οιρίν,το, 435), the female is called λόττα/λοττού (lótta/lottoú) (Petrou-Poiitou 2013, entry Λόττα, λοττού, 78).

Every family would raise a pig in the backyard of the house that would be fed for 5-6 months with leftover food and a mixture of bran and whey. The pig would grow old enough until around New Year's Day, so, on New Year's Eve, the butcher would go to the house, slaughter the pig and cut it into pieces (Agia Varvara Primary School 1991, 45).

Functional and symbolic role

Every family would raise a pig, which would usually be slaughtered at around Christmas time and its meat would be eaten throughout the year.

Households would buy a pig from the villages of Karpasia, Tillyria and Akamas in the Paphos district, where there were pig farms. A pig would be slaughtered when it was about one year old. Cypriots considered a pig older than 12 months old not edible (Xioutas 1978, 138, 146). By processing the meat, households would secure enough charcuterie (sausages, cured meats, hiromeri, posyrti and lountza) as well as myllan (cooking fat) for a whole year (Xioutas 1978, 148-157).

The period during which pigs were slaughtered was called Soirophaáes and lasted from 12 December (St. Spyridon's Day) to 6 January (Epiphany) (Xioutas 1978, 138, 146). In some areas, pigs were slaughtered during Carnival, just before the beginning of the Easter fasting period. The slaughter of a pig was a ritual in which the whole family, relatives and friends would participate (Kyriakou 2004). Following the sort-out of the meat parts, a feast would follow with the participation of all those present (Papacharalambous 1965, 177). The housewife would barbecue the liver and the vlantz̆ín, i.e. the lungs, on charcoal. Each person would taste a small piece of meat accompanied by wine. In the area of Pitsilia, the feast was called 'pariorká' (Xioutas 1978, 148).

The families with no animals would buy a female pig, which they would call lottoú or daskaloú (teacher), because the family's revenue from this animal was equivalent to or even more than a young teacher's annual salary (Xioutas 1978, 138).

Additional information and bibliography

We see that every part of the animal, even the theoretically useless parts, such as the ears, intestines and legs were important and useful. Almost every bit of the animal would be turned into food.

Yangoullis K. G. (2014), Θησαυρός Κυπριακής Διαλέκτου. Ερμηνευτικό, Ετυμολογικό, Φρασεολογικό και Ονοματολογικό Λεξικό της Μεσαιωνικής και Νεότερης Κυπριακής Διαλέκτου, Βιβλιοθήκη Κυπρίων Λαϊκών Ποιητών, Theopress Publications, Nicosia.

Ayia Varvara Primary School (1991), Ayia Varvara, Nicosia.

Kyriacou D. (2004) Το χωριό μου η Ξυλοτύμπου, A. Alonefti press, Nicosia.

Petrou-Poeitou E. (2013), Από πού κρατάει η σκούφια τους. Λέξεις και ιστορίες από τον κόσμο της γεύσης, Epiphaniou Publications, Nicosia.

Xioutas P. (1978), Κυπριακή λαογραφία των ζώων. Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XXXVIII, Nicosia.

Eleni Christou, Stalo Lazarou, Demetra Demetriou, Argyro Xenophontos, Tonia Ioakim