Pishíes were a customary preparation of dough that were prepared on many occasions and served with sugar, honey or carob syrup.

Name - Origin

They are thin pittas made of dough, fried, with sugar or honey (Yangoullis 2009, entry πισ̆ία,η, 362). They are also eaten with syrup (Petrou-Poeitou 2013, entry Πισιήδες, 116), while Xenophon P. Pharmakidis mentions that, apart from sugar, they can also be sprinkled with teratsomelo (carob syrup) (Kypri 1983 [2003²], entry πισ̆ίδες,οι, 32).

ETYM. < turk. pişmek (Yangoullis 2009, entry πισ̆ία,η, 362) Petrou-Poeitou notes that the word derives from Ancient Greek epichydes or epichytoi plakountes. Pisi in Turkey are pancakes made of yeast dough (Petrou-Poeitou 2013, entry Πισιήδες, 116).

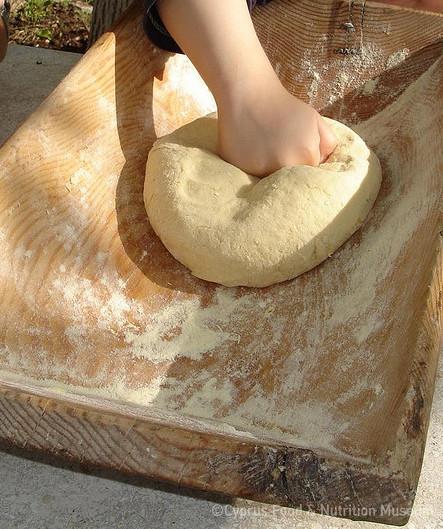

Pishíes, made of dough, were either fried or baked on satz̆in [satz̆i = cooking utensil, a shallow clay tray with two handles or a metal plate on which pittas were baked]. Sometimes, they were made with sourdough starter. Sometimes fat was used, depending on the occasion. Pishies were fried either in olive oil or in pig fat, depending on availability (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, pp. 246-247, 254).

Pishies were made of dough, fried and then dipped in syrup. They were given various shapes such as bows, ppaklavá (baklava] shape, glytžistá, glytžistikón, traaná or sapsádes in triangular shape. Pishíes often would consist of several dough sheets and were called kattimérka. In some villages of Mesaoria, they would prepare millópittes; they would spread over some milk butter, then wrap them and bake them in the oven. They used to make glytz̆ista or dáhtyla (ladies' fingers); they would spread some ground almonds, sugar, cinnamon and rosewater on a dough sheet, shape it accordingly and fry the glytz̆ista or dáhtyla and then dip them in syrup. In some villages in the Limassol district, such as Kilani, they would sprinkle pishies with sesame seeds instead of ground almonds (Protopapa 2009, pp. 310-313, 318).

Search for many pishies variations in the Traditional Recipes section, entry keyword: pishies.

Functional and symbolic role

Pishies would be served with a sprinkle of sugar or a drizzle of honey or carob syrup. In Morphou [occupied municipality of the Nicosia district], pishies would be prepared whenever olive oil was extracted, so as to fry them in the first first batch of olive oil. In Lapithos [occupied community of the Kyrenia district] they would fry them in the last batch of olive oil that they would bring to the house (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, p. 254).

Pishies were offered in many occasions: after childbirth, as a gift to the new mother by the future godparents (Protopapa, 2009 pp. 310-313, 318) and also as a treat from the new mother to her friends and relatives (Leontiou 1983, 176; Kypri - Protopapa 2003, p.167), as part of the sweetmeats prepared for a christening or a wedding (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, pp.169, 175, 217).

Pishies were also prepared at potherká (the feast held at the end of the harvest), and to be consumed amongst groups of friends that would gather to clean cotton wool (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, p. 292).

Pishies were prepared on the Feast of Agioi Saranta (40 Saints, 9th of March). On the eve of the feast, they would prepare 40 small pishies that they would take to the church service and then they would distribute them amongst the people who were present. In the area of Morphou, it was customary, on this day, to offer pishies to the neighbours (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, p. 141).

On the day of the feast of Saints Peter and Paul (29th of June), it was customary in Sykrasi [an occupied community of Famagusta district] to fry pishies in samólado [sesame oil], to adhere to fasting, as ay other type of oil was 'forbidden' (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, p. 145).

On the Feast of the Presentation of Mary (21st of November), people would prepare pishies in many villages. In the village of Akanthou [occupied community of Famagusta district], they would make pishies lytrantz̆énes [without starter/yeast], which they would fry in fresh olive oil, as this was the time when fresh olive oil would be exported (Kypri - Protopapa 2003, p. 151).

Additional information and bibliography

Yangoullis K. G. (2009), Θησαυρός Κυπριακής Διαλέκτου. Ερμηνευτικό, Ετυμολογικό, Φρασεολογικό και Ονοματολογικό Λεξικό της Μεσαιωνικής και Νεότερης Κυπριακής Διαλέκτου, Βιβλιοθήκη Κυπρίων Λαϊκών Ποιητών, 70, Theopress Publications, Nicosia.

Kypri Th. D. (ed.) (1983 [2003²]), Υλικά διά την σύνταξιν ιστορικού λεξικού της κυπριακής διαλέκτου, Μέρος Β΄, Γλωσσάριον Ξενοφώντος Π. Φαρμακίδου, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, IX, Nicosia.

Kypri Th. - Protopapa K. A. (2003), Παραδοσιακά ζυμώματα της Κύπρου. Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XVIII, Nicosia.

Leontiou N. (ed.) (1983), Άσσια. Ζωντανές μνήμες, βαθιές ρίζες, μηνύματα επιστροφής, "Assia" Cultural Association, Nicosia.

Protopapa K. (2009), Τα έθιμα της γέννησης στην παραδοσιακή κοινωνία της Κύπρου, Publications of the Centre for Scientific Research, XLIX, Nicosia.

Petrou-Poeitou E. (2013), Από πού κρατάει η σκούφια τους. Λέξεις και ιστορίες από τον κόσμο της γεύσης, Epiphaniou Publications, Nicosia.

Stalo Lazarou, Varvara Yangou, Demetra Demetriou, Tonia Ioakim, Argyro Xenophontos